Posted on October 01, 2024

The European Patent Office (EPO) opens its guidelines on inventive step by saying:

The term "obvious" means… something which does not involve the exercise of any skill or ability beyond that to be expected of the person skilled in the art. - EPO Guidelines March 2024 Ed, G-VII 5.

The EPO has developed a framework known as the “problem-solution approach” to provide an objective way to assess whether a claimed invention is obvious. This is done by evaluating whether the prior art points to the claimed features as solving an “objective technical problem”.

To summarise, the problem-solution roadmap involves:

This is the second in a series of two articles. The first article reviewed each stage of the roadmap in turn and provided practical advice for applicants seeking patent protection in Europe.

This second article goes through the approach using a worked example from the field of textiles. It also provides a brief comment, for interest, on the somewhat different legal framework recently adopted in post-grant proceedings in Europe, at the new Unified Patent Court, for the inventive step assessment.

Worked example using the problem solution approach – the scenario

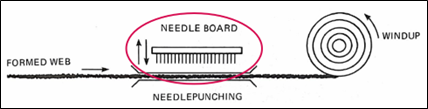

A client has arrived at an innovative piece of nonwoven textile machinery. Instead of a conventional flat needle board for needlepunching nonwovens, they have produced apparatus comprising a needle board shaped as a segment of the surface of a sphere:

The new shape of the board enables the board to be rocked in several directions. The apparatus can therefore be used to exert lateral and/or vertical punching force. This improves control over the density of fibers in the resulting non-woven, compared to movement in one direction.

The application as filed contains evidence showing the improvement compared to the conventional flat needle board, which can only exert punching force in one direction (the vertical).

The cited prior art and choice of closest prior art

The Examiner has cited three pieces of prior art: D1, D2 and D3.

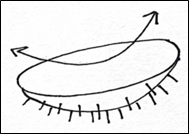

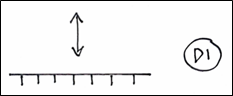

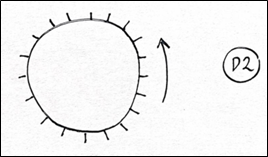

In this scenario, the closest prior art is D2, because it is in the same field (nonwovens) and has a similar purpose (patent application aim: better control over nonwoven density; D2: provide a more uniform nonwoven density). Even though D3 is seemingly closer in structure, it is distant in field and purpose. Meanwhile, D1 is in the same field, but is further removed in structure.

The distinguishing features over the closest prior art, their technical effect and the objective technical problem to be solved

Distinguishing features over the cylindrical roller of D2 include, at least, the shape of the claimed board.

The different-shaped board provides a different type of needle punching motion: multi-directional rocking, rather than unidirectional rolling.

The evidence provided in the application shows that when a rocking motion is employed, the non-woven density can be modulated in a manner not achievable when the punching motion is only in one direction. Although this evidence is comparative with D1 rather than D2, it does provide evidence about the advantages of the multi-directional rocking over unidirectionality, which may help with the argument over D2.

We can frame the direct technical effect of the difference in board shape as being to provide a way to control the nonwoven density.

We can therefore formulate the objective technical problem as how to improve control over nonwoven density.

Why the claimed solution to the problem is not obvious

We can argue that the claimed solution is not obvious when considering D2 alone, even when the common general knowledge of the skilled person is taken into account, because there is no disclosure or suggestion of the shape of the claimed board in D2. D2 teaches using a cylindrical roller for a more uniform process, so that it can be said to teach away from non-continuous rocking. There is nothing to suggest a rocking motion provided by a sphere segment shaped board – a smooth roller motion is used instead.

Combining D2 with D1: D1 still does not disclose the missing feature. There is also a structural incompatibility with D2 (a flat board vs. a roller). D1 provides no incentive to modify the structure of D2 to improve control over nonwoven density, by making a rocking needle board.

Combining D2 with D3: D3 is in a different field, of knitting not nonwovens. There is nothing in D3 to suggest the skilled person should repurpose its rocking bed of knitting needles in a totally different application (it is only taught for 3D knits). There is also a structural incompatibility (technical hindrance to combine D2 with D3), as many further modifications are required to go from knitting apparatus to something suitable for nonwovens.

As noted in the first article in this series, at the EPO, one would not normally combine all three of D2, D1 and D3. There is an exception to this rule, known as “partial problems”. (See the first article for an explanation.) There is only one objective technical problem here, so “partial problems” does not apply. Therefore, we do not need to consider the combination of D2 with both D1 and D3.

All in all, we can say that the requirements for inventive step are met.

A final note: a new approach may be emerging at the Unified Patent Court

Although this series is predominantly focused on the EPO approach, it is worth a brief comment on the different approach recently adopted in post-grant proceedings in Europe, at the new Unified Patent Court.

At the EPO, the problem-solution approach is used in all proceedings – whether the EPO is International Preliminary Examination Authority in the International (PCT) phase; during direct or regional phase prosecution in Europe; in oppositions; and in appeal proceedings.

However, in the Munich Central Division of the new, centralised Unified Patent Court (the UPC, which opened its doors for business just over a year ago, at the time of writing), a new approach has been adopted - in certain significant cases - which diverges from the EPO problem-solution approach. Specifically, in 10x Genomics and Harvard v Nanostring (UPC_CoA_335/2023) and Sanofi v Amgen (UPC_1/2023), the following test has been applied:

- identify a realistic starting point; and

- compare the claimed subject matter and prior art to determine whether it would be obvious for the skilled person to, starting from a realistic prior art disclosure, in view of the underlying problem, arrive at the claimed solution.

A starting point will be considered realistic if “its teaching would have been of interest to a skilled person who, at the priority date, was seeking to develop a similar product or method to that disclosed in the prior art which thus has a similar underlying problem as the claimed invention.”

As to obviousness, “a claimed solution is obvious if, starting from the prior art, the skilled person would be motivated … i.e. have an incentive to consider the claimed solution and to implement it as a next step in developing the prior art”.

We have seen a more EPO-style approach (including a step of determining “objective technical problem”), yet without strict adherence to the problem-solution approach, being taken by the Paris Local Division (DexCom v Abbott ,UPC_CFI_230/2023) and the Düsseldorf Local Division (Franz Kaldewei v Bette, UPC_CFI_7/2023).

It remains to be seen whether the UPC will re-align to adopt a more similar approach to the EPO, or whether this divergence is here to stay. It is also not yet clear whether drafters of patent applications should be doing anything differently – compared to the considerations made under the problem-solution approach – to take the UPC approach into account. Watch this space.

This article does not constitute legal advice. For assistance in patent matters, please get in touch with the author or reach out to your usual contact at Abel + Imray.

You can read Part 1: Inventive step at the EPO here.